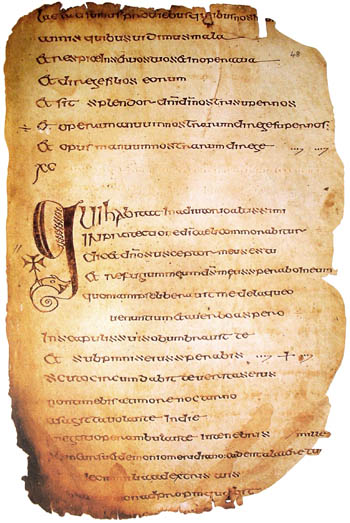

The Cathach

Because copyright has a long history which has developed piecemeal, this has to include the years before photography. The concept of copyright has been around for a long time and on the whole, the principles haven’t changed much. The Ancient Greeks and Romans were keen to protect their rights but it wasn’t easy to work out a method when everything was written by hand or carved in stone. The earliest reference is the blessed St Columba, a monk who was born in Co Donegal on 7 December 521 AD and lived in Movilla Abbey in Co Down. His master, St Finnian , owned a psalter which had come from Rome, a uniquely hand decorated copy of a Book of Psalms translated into Latin by St Jerome. St Columba coveted a copy. St Finnian refused to let him make one. St Columba wasn’t inclined to take no for an answer so he borrowed it and copied it surreptitiously. St Finnian found out, hauled him before King Diarmait and demanded the new copy as stolen property. On the whole, copying manuscripts was what monks did but not necessarily for their own personal use. This copy still exists and lives in The National Museum of Ireland. It’s written on vellum, is called The Cathach and there are about fifty-eight pages of it. It’s there because King Diarmait declared ‘To every cow her calf; to every book its copy’ and confiscated it. His declaration was presumably either in Gaelic or Latin and the translation may be suspect but it would seem to be the very first copyright judgment. St Columba wasn’t happy, raised an army, attacked and defeated King Diarmait, three thousand corpses littered the field and St Columba, mortified, exiled himself to Iona to do penance, built the monastery which is still there and set about converting the Scots - but he never recovered his copy of the psalter. He also had an adventure with the Loch Ness Monster but that’s another story.

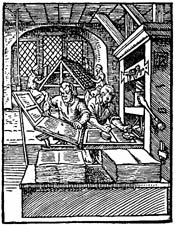

Printing as we know it didn’t arrive until the fifteenth century and with it came problems. Books quickly became easy to print and not expensive. William Caxton set up the first printing press in Westminster in 1476 and several others quickly followed. When it was clear that a book was an economic success, it was all too easy to rip off the printer next door. Although a lot of the early printing was small broadsheets, not far removed from the junk mail of today, there were rich pickings to be made from producing cheap copies of The Canterbury Tales.

Printing as we know it didn’t arrive until the fifteenth century and with it came problems. Books quickly became easy to print and not expensive. William Caxton set up the first printing press in Westminster in 1476 and several others quickly followed. When it was clear that a book was an economic success, it was all too easy to rip off the printer next door. Although a lot of the early printing was small broadsheets, not far removed from the junk mail of today, there were rich pickings to be made from producing cheap copies of The Canterbury Tales.

Venice and the Papal States were well ahead of everyone else when it came to protecting rights. Before about 1700, there was no copyright law in what we now call the British Isles. The Crown was always impecunious, always greedy and always suspicious and there was money to be made from selling licences to printers and political advantage to be gained from censoring the seditious things printers were apt to publish, thus killing two birds with one stone. The first licence was issued in 1518 to Richard Pynson, the King’s printer - the Crown didn’t waste a lot of time before lining their coffers after Caxton first introduced printing from movable type. Authors collected a limited right to a share of the profits made by pirated copies but even this had to be shared with the Crown. After 1662, nothing could be published which hadn’t been registered with the Stationers Company.

The first real British copyright act was the Statute of Anne in 1709 applying in England and Wales. This concerned books only and not prints or engravings. Authors had the sole printing right for fourteen years which could be extended by another fourteen years if the author was still alive when the time ran out. If there was no extension, the book was fair game. Authors whose books were already in print got twenty one years and everything still had to be registered with the Stationers Company.

In 1777, JC Bach sued a publisher for reproducing a harpsichord sonata. Lord Mansfield (MP, Solicitor General, Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas), said ‘A person may use the copy by playing it but he has no right to rob the author of the profit by multiplying copies and disposing of them to his own use.’ This principle has been with us ever since and still influences both Courts and Parliament. What this means to us is that you can look at a photograph and you can own a photograph but you cannot profit from copying or publishing a photograph without permission from the copyright holder.

The Statute of Anne continued for many years with additions when necessary. In 1814, the time was extended to twenty eight years from the date of publication and if the author was alive after that time, his rights were extended until he died. In 1842 authors got life plus seven years or forty two years from publication, whichever was the longer - and it was no longer necessary to register with the Stationers Company.

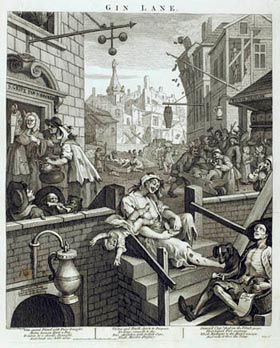

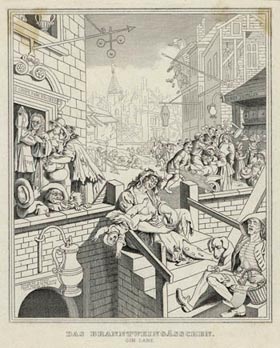

The original Hogarth engraving.

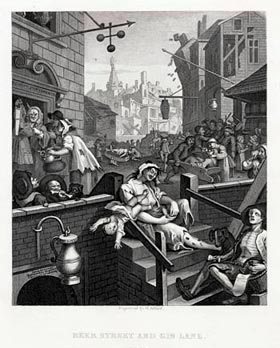

A pirated version by Adlard.

A terrible German version.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Prints and engravings had to wait for William Hogarth. As soon as one of his engravings was published, rival print shops pirated them and sold cheap, inferior copies. The Engraving Copyright Act 1734 gave engravers rights for fourteen years and the Act, implemented on 25 June 1735, was usually referred to as ‘Hogarth’s Act’. In 1766, a second Act gave people like Hogarth’s widow rights for twenty eight years. Without this, she and others in her position would have been destitute. Printers still pirated anything they fancied and got round the Act by making small changes to the original so in 1777 came another Act which cleaned up the details by stopping anyone copying anything ‘in whole or in part’ which more or less stopped the pirates. In 1852, lithographs which were a steadily developing printing method, were added to the list along with other mechanical processes.

By which time, there was also photography.